Specialized Commodities During Income Plateaus

Consider the following scenario: Several years into a period of flat incomes, producers are beginning to wonder how to diversify their operations. Producers are showing a rising interest in one specialized commodity that could bring in substantial profits with relatively limited capital investment. The market for the commodity isn’t fully developed, but strong growth in consumer demand is anticipated. There are concerns around potential regulatory change and processing costs, but it is assumed the industry will rise to meet these challenges as it matures. The year is 1988, and many American ranchers across the south are about to begin raising ostriches.

The Rise and Fall of the American Ostrich Industry

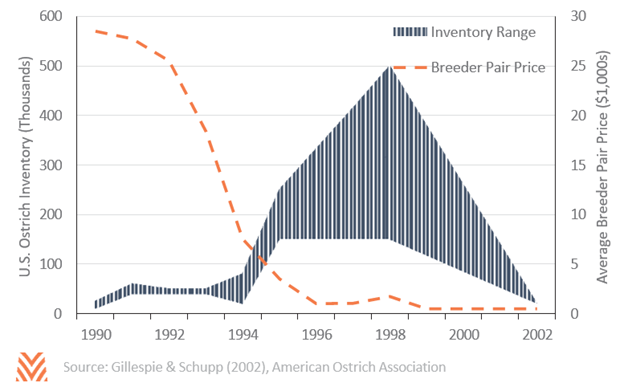

Data surrounding the ostrich boom are rare, but a combination of industry estimates and contemporary studies show the volatility of the industry. In 1989, speculation for ostrich breeder pairs reached a peak after the USDA placed an embargo on South African imports due to fears related to livestock diseases transmitted by ticks. Breeders sold ostriches for upwards of $40,000 a pair due to speculation about the potential size of the U.S. market and restrictions on ostrich imports.

As ostrich production slowly increased, prices for the ratites began to fall. Processing costs remained very high, despite elevated inventories. The consumer market did not grow as quickly as anticipated, in part due to high retail prices brought on by processing costs. In late 1996, the industry saw an opening after the rise of mad cow disease in the United Kingdom, which some believed would entice consumers to eat more ostrich meat. Around the same time, the USDA eased its restrictions on ostrich imports, allowing inventories to grow considerably in a very short time. One industry member estimated that as many as 500,000 ostriches were in the United States in 1998.

Prices for ostriches, which had been falling for years, dropped considerably due to oversupply. Consumers in the United Kingdom did not switch to ostrich meat en masse, driving prices down lower. By the end of the decade, the birds were so costly relative to their value that many producers simply released their ostriches into the wild. By the time the Census of Agriculture first asked producers about ostrich production in 2002, only 20,000 birds remained on farms. Today, the American ostrich industry has stabilized into a niche market, but many of its participants believe that an initial opportunity was missed.

Potential Parallels to Industrial Hemp

Ostriches have little in common with industrial hemp, but several of the challenges facing the budding hemp industry are like what faced ostrich producers in the 1990s. Specifically, hemp sees a trio of similar challenges: navigating regulatory change, addressing processing costs, and growing consumer demand.

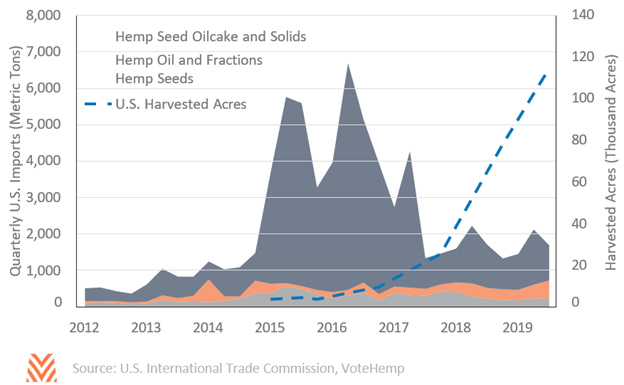

Regulatory change can impact hemp production in two ways. First, regulators can slow the demand growth of hemp through rulings limiting the market opportunities for cannabidiol products. The hemp industry witnessed this in November, when the U.S Food and Drug Administration issued a ruling that it could not conclude that cannabidiol products are generally recognized as safe for consumption. However, the hemp industry has several advantages over the 1990’s ratite market. First, the industry has created a series of trade associations and interest groups that are more organized than earlier specialized commodities. Second, while the ostrich industry notes that they faced some competition from other animal and animal product trade groups, CBD products have fewer, less powerful detractors. However, regulatory change can also produce challenges by allowing producers to rapidly enter a new market. The restriction on ostrich egg and bird imports in 1996 led to an almost immediate oversupply of the birds, leading to a price collapse as demand growth failed to keep up with the additional supply. Since the 2014 farm bill allowed for hemp pilot programs, harvested acres of hemp have increased from zero initially to an estimated 127 thousand acres in 2019, and over 500 thousand acres were licensed for potential production.

A second challenge that faced the ostrich industry was high processing costs that did not come down sufficiently to justify the expense for consumers. One study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison noted that hemp may face the same issue, noting that it could be less profitable than other specialty crops due to the “…current state of harvesting and processing technologies, which are quite labor-intensive.” Traditional retting and fiber-separation processes are both labor- and resource-intensive, but newer solutions such as cold storage or wet baling have shown some promise in reducing costs.

Finally, producers should pay close attention to consumer demand growth. One study noted that sales of hemp- derived products in the U.S. have grown from $49 million in 2014 to $264 million in 2018, driven predominantly by growth in CBD products. Estimates of future growth anticipate sales to continue growing annually between 20% and 30% over the next several years, with a market for all hemp-derived, marijuana-derived, and pharmaceutical CBD products nearing $2 billion by 2022. This growth, if realized, would go a long way towards justifying additional U.S. hemp production.

Industrial hemp may face some of the same challenges that earlier commodities have seen, but the young industry has shown that it is making strides towards addressing regulatory, processing, and consumer demand concerns. Hemp product sales may not continue the rapid growth we have seen over the last several years, but hemp production could offer producers a way to diversify their incomes during the current period of lower net farm incomes.