Global Food Prices and Export Risks

Agricultural exports are a primary reason why the U.S. farm economy is in the robust shape it is today. In an era of global production challenges and geopolitical uncertainty, American production is essential for myriad countries across the globe. The United States is a critical supplier of agricultural commodities to the Americas, the Middle East, Asia, and the Central African coast. In other regions, like India and the European Union, the United States fills important niche roles through its production of consumer-oriented foods like fruits, nuts, and vegetables.

The diverse nature of America’s partners means that American products are sold to a broad set of consumers. Dairy exemplifies the heterogeneous nature of America’s export partners. For example, the largest dairy export partner in 2021, Mexico, predominantly imported non-fat dry milk (though they see this as an inferior good that they hope to replace with liquid milk). Canada, our second-largest partner, imported higher-value consumer products, like infant formula, whey protein drinks, and other consumer-oriented products. And our third largest partner, China, imported whey protein powders used as feed for piglets. It is important to note that the varied nature of these countries’ use of American dairy products also implies that they will respond differently to rising prices.

Food Costs

While prices have already been increasing over the last two years, the Russia-Ukraine conflict has led to an acceleration in global food prices. In addition to the direct impacts of the conflict on Ukrainian production, it has also led to an increase in global fertilizer costs and inflamed the shipping constraints that have already plagued the sector. As nations begin to worry about their ability to feed their populations, many have begun enacting restrictions on the export of agricultural inputs and commodities. Some major grain exporting countries, like India, have announced a ban on exports to control inflationary pressures. At the same time, Southeast Asia and parts of Europe are experiencing a renewed outbreak of African Swine Fever, widening the global protein deficit.

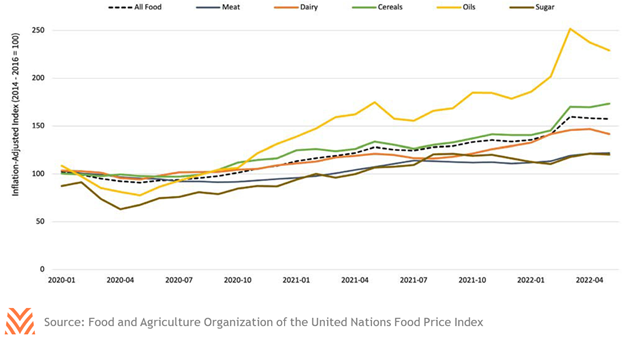

These factors have contributed to the explosion in global food costs—but there is some potential upside for U.S. producers. The U.S. is uniquely positioned to make up for some global deficits, which is partially why the USDA’s Economic Research Service has projected that U.S. agricultural exports will reach a record $191 billion in the 2022 fiscal year. The key obstacle to this record export value may be cost. The figure below shows the Food and Agricultural Organization’s global price index for various agricultural commodities. The current crises have put global food prices at all-time real highs (i.e., adjusted for inflation), eclipsing the 1970s wheat crisis. Complicating these cost increases are the rising U.S. dollar and threats to global growth. Both prices and exchange rates have the potential to reduce global demand, and both factors will be felt differently depending on what commodities and partners are involved.

Exchange Rates

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the U.S. dollar index has seen consistent growth, and as global growth expectations sputter, investors have flocked to the relative safety of the dollar. However, specifics matter in how exchange rates influence agricultural imports. The primary difference relates to whether a currency is devaluing against the dollar specifically, or whether it is losing ground to many currencies at once.

The U.S.-Japanese trade relationship has given us examples of both types of devaluation over the last decade. Japan imports a substantial amount of products from Oceanic countries like New Zealand and Australia. Over the last year, the Japanese yen fell against the currencies of both the U.S. dollar and Oceanic currencies, meaning that Japan could not replace more expensive U.S. products with relatively cheaper products from New Zealand or Australia. On the other hand, the U.S. dollar strengthened against both the yen and the Australian dollar between 2013 and 2014. This relative advantage was one of the drivers of the 2014 Japan-Australia Economic Partnership Agreement which, along with the relative cost of U.S. beef, led to the decline of almost a fifth of U.S. beef exports to Japan during this period.

Global Growth

In its April forecasts for global growth, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reduced its growth expectations for 2022 from 4.4% to 3.6%. While the IMF projections decreased emerging market growth by far more than advanced economy growth, this was driven by large forecast declines in the Russian economy. Of the U.S.’s top agricultural export destinations, Canada, China, and ASEAN nations saw smaller declines, while Japan, Europe, and Mexico saw larger ones.

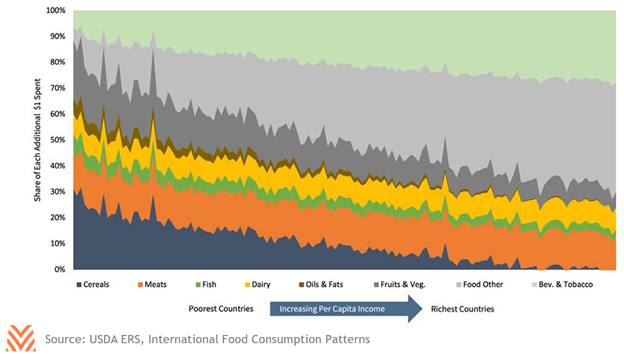

Changes in growth expectations will likely not impact all nations equally. The figure below shows how each country spends an additional dollar on food, sorted by per capita income. The wealthiest nations spend upwards of 70% of an additional dollar on beverages, food away from home, and high-end consumer-oriented goods like cheese and beef. On the other hand, the poorest nations spend the plurality of an extra dollar on grains. During times of strain, individuals in emerging economies might conserve calories by spending a greater share of their food budget on grains and less on proteins, while individuals in wealthier nations have more slack.

As we wrote in the spring 2022 issue of The Feed, American consumers often don’t change their food buying habits in response to price changes; rising prices (or falling incomes) have a muted impact on total consumption in wealthy nations. This is less true in the developing world, where rising costs or falling incomes can have a much more significant impact. For example, one 2014 USDA study found that in India, a 10% rise in the price of beef was associated with a roughly 5% decline in total consumption, compared to only a 1.5% decline for U.S. consumers. In other words, while wealthy economies may see a negligible impact on imports because of rising costs, developing nations are more likely to change consumption patterns for most commodities. That said, consumers in low-income countries will still have inelastic demand for staple goods like rice or wheat, continuing to stock up on those important calorie sources.

American exports are likely to be a critical source of support for many countries this year. The rising dollar and slowing growth will be headwinds, but context matters. Slower growth and weaker currencies might not have a significant impact on agricultural consumption in advanced economies, but those wealthier nations could seek alternative sources if exchange rates create an opportunity. Meanwhile, developing economies are more likely to respond to slow growth or weak currencies, although proteins and consumer-oriented goods are more at risk than staple goods. Knowing the products and players for each partnership can help explain the potential risks of a given relationship. Exports are likely to remain a critical source of support for America’s farmers and ranchers, but understanding the dynamics of global trade can help some of the headwinds we are likely to see in the coming years.