Climate Patterns and Extreme Weather

In recent years, America’s farmers and ranchers have been buffeted by extreme weather events. These events led both Secretaries Purdue and Vilsack to the same conclusion: that climate change is a serious risk to American producers’ bottom line. Some of these risks are already being realized in the form of recent historic floods and fires. Other risks, like widespread heat stress from rising temperatures, may still be far off. While producers are already adjusting to changing weather patterns, the greatest impacts to production likely have yet to occur.

Extreme Weather Events

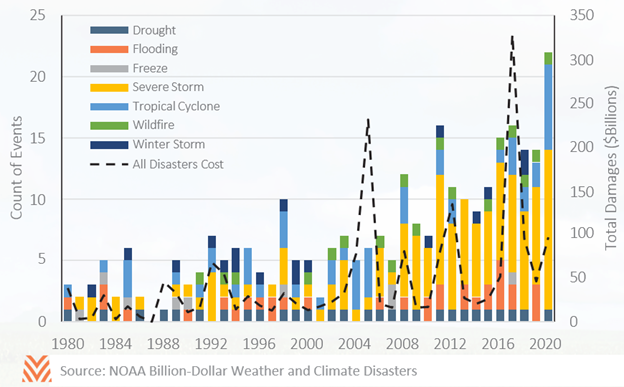

The most immediate climate threat to America’s producers is from extreme weather events. The number of catastrophic weather events has steadily increased from an average of two per year in the 1980s to over 20 last year. These events are not exclusive to any one region. In the last three years, every major growing region has experienced at least one type of extreme weather event. The increasing frequency and cost of these events means higher potential for failed crops, prevented acres, lower yields, or more expenses to mitigate these risks.

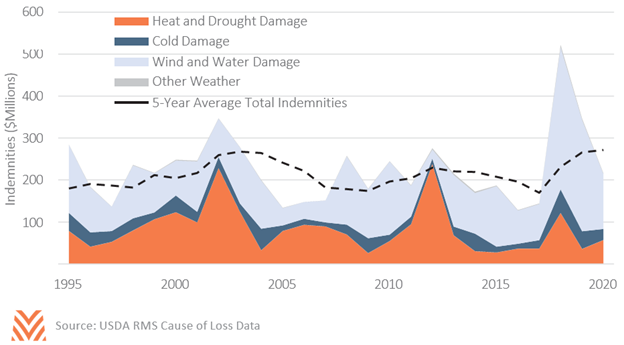

While climate change is not the sole cause of any one weather pattern, it exacerbates most weather challenges producers face. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has found that temperature increases lead to greater rainfall, making a bad flooding year like 2019 even worse. Rising temperatures can also increase the wind speed and size of hurricanes, threatening more producers in the south and southeast. Even cold weather events, like the February freeze in Texas, may be made worse by warming temperatures. Warm winters can lead to greater polar wind variability, allowing arctic winds to push further south than they would have otherwise. These events are already threatening producer incomes. Farmers reported more than 19 million acres in prevent plant in 2019, more the double the prior record. USDA Risk Management Agency data find that corn and soybean indemnities for weather-related loss reached new highs in the last few years. This increase in weather- related crop loss indicates that producers are already seeing some impacts from a changing climate.

Production Risk

Not all climate risk is immediate. A broader long-term risk stems from impacts to yields from heat stress. To date, the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) has found that temperature increases over the last century have been lowest in major agricultural regions like the western Corn Belt and around the Gulf of Mexico. Many of these areas have experienced no more than one degree of warming Fahrenheit between 1900 and 2020. Conversely, the West Coast and northern Great Plains have seen some of the highest temperature increases over this time, which has contributed to recent drought and wildfire challenges.

Over time, these increased temperatures can pose many problems for producers. The USDA has estimated that total acres for corn will fall between 7 and 12 percent by 2080 as temperatures rise, with many non-irrigated acres projected to need to convert to irrigated acres. Revenue protection program premiums are forecast to more than double in many regions. Yield variability will increase as less-predictable weather patterns lead to greater variation from year to year.

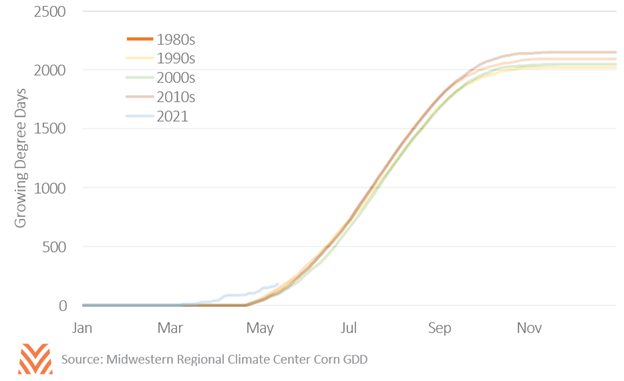

This does not mean that producers have seen these risks yet, or that all producers will experience the same challenges. A review of corn growing degree days (GDDs) in parts of the country that the EPA says have seen the greatest warming does suggest rising temperatures. The figure below shows GDDs over the last few decades for a county in northern Minnesota. The last decade was the warmest on record, and 2021 has started at a historic pace. However, a review of county average yields finds that the warmest years have also been some of the county’s best for corn yields, suggesting limited evidence of heat stress. In short, this area is so far north that the additional GDDs may have not been negative for corn yields, even if that is not true for more southern growing regions.

Other commodities or regions will see some changes in the near term as producers seek to mitigate climate change risk. The USDA ERS estimates that warming temperatures will cost the dairy industry between $80 and $200 million per year in heat-stress related production loss by 2030. Most dairies will also see higher energy expenditures as they use more cooling mechanisms. For crops, higher temperatures have contributed to the widespread adoption of drought-tolerant variants, leading to higher seed costs. The premium on irrigated acres is likely to continue to rise as drought and water access issues impact producers. For many commodities, climate changes will manifest first as increased production expenses rather than as direct impacts on yields or yield variability.

For many years, climate change was perceived as a homogeneous force that would lead to universal impacts, such as flat temperature increases or changes in sea level. The reality has been much more nuanced. America’s producers have experienced a stable climate for the last 250 years that is likely to give way to increased volatility as temperatures rise. Producers will be able to mitigate much of that risk, but the costs will eat into producers’ bottom lines even in years where volatile weather doesn’t impact yields. As always, farmers and ranchers will have to be aggressive and innovative to adapt to a changing environment.