What in the World? How the U.S. Became a Net Importer of Food and Agriculture

Since the 1990s, the U.S. consumer has increasingly relied on imports to fulfill a growing and diversifying demand, especially for durable goods like apparel, electronics, and household furnishings. At the same time, corporations linked together international supply chains in search of lower labor costs and increased production efficiencies, especially for large, complex manufacturing items like automobiles, mobile phones, and apparel. The result has been a widening gap between goods exported and goods imported, commonly referred to as a trade deficit. Many economists argue that a trade deficit is not necessarily a bad thing, as trade allows global economies to specialize in relative advantages (e.g., one country with more widely available labor and another with more widely available natural resources) and produce more trading together than alone in isolation. However, trade deficits can also be divisive if lower-cost foreign production threatens domestic industries that are vital to the nation’s economy or security.

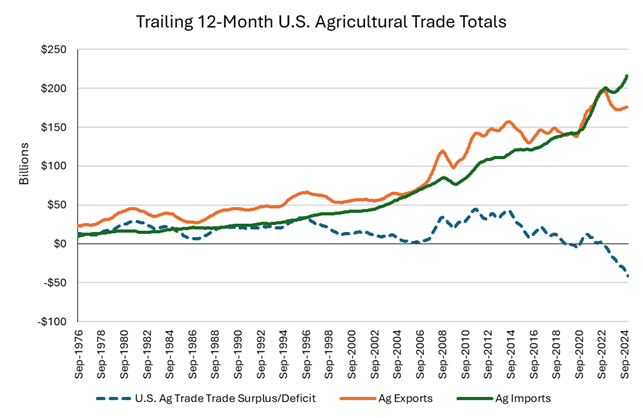

For decades, stakeholders in the U.S. food and agricultural supply chain took pride in the fact that the U.S. was a net exporter of bulk and consumer food products. The USDA has tracked farm and food trade statistics back to 1975. For more than 40 years of this trade history, the U.S. exported more agricultural products than it imported. Farmers viewed this trade surplus as our superpower: to feed the world with the most efficient production, safest standards, and highest quality. And while American agricultural and food producers maintain that superpower today, the U.S. is no longer a net exporter of food. Beginning in 2020, food imports into the U.S. began to edge out exports, and in December 2024, the trailing 12-month net trade balance fell to a record $40.7 billion deficit.

Ag Trade Kryptonite

When cracking the complexities of global trade dynamics, it can be a good idea to first examine exports. If exports fall faster than imports for a long enough period, there will eventually be a trade deficit. While U.S. agricultural exports have fallen in the last three years, there have been several periods in which U.S. food and ag exports fell faster or for longer than the period from 2022 to 2024. These notable periods, the mid-1980s, the early 2000s, and the mid-2010s, were all associated with stressful periods in the agricultural economy, but none of them resulted in an agricultural trade deficit.

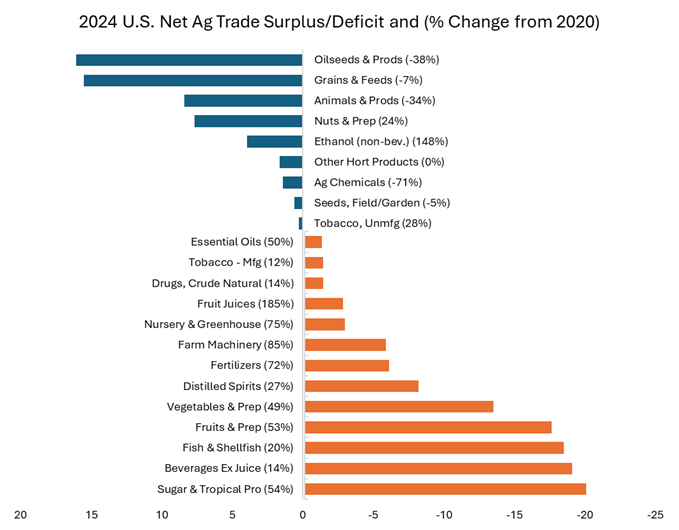

So, if falling exports aren’t the driver of the U.S. agricultural trade deficit, the source must be imports. Indeed, the U.S. consumer has been on a food import spending spree since 2020. Between 1980 and 2020, U.S. food imports increased at an average annual rate of 6% per year; starting in 2021, that rate has jumped up to approximately 10% per year of growth. While the U.S. maintains strong trade surpluses in bulk commodities and land animal proteins and products, consumers have asked for increased access to fruits, vegetables, seafood, and horticultural products. Many of these food categories are not well suited to U.S. production (e.g., bananas, coffee, many seafood varieties, and many beverage categories), or consumers have become accustomed to year-round availability of seasonal grocery items (e.g., blueberries, tomatoes, melons, and many vegetables). Trade allows the U.S. consumer to have greater access to a diversity of food categories for a high percentage of the calendar year. And since 2021, U.S. consumers have had unfettered access to global markets, sometimes to the chagrin of U.S.-based producers making the same products (just ask a Florida tomato grower who has been competing with Mexican tomato producers for the last several decades).

The ‘ABCs’ of the DXY (US Dollar Index)

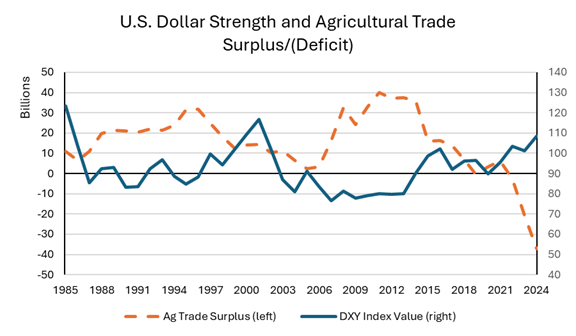

Exchange rates matter a great deal in foreign commerce. When the U.S. dollar is weak relative to other currencies like the euro, the Japanese yen, the Mexican peso, or the Chinese renminbi, the U.S. consumer can afford less of the foreign goods. The importer of Mexican tomatoes must convert U.S. dollars to Mexican pesos, and if the U.S. dollar is weak, the Mexican tomatoes become more expensive, and the importer must raise their selling prices to cover the higher costs. Meanwhile, foreign buyers of U.S. agricultural goods have greater buying power when the U.S. dollar is weak, and can afford more U.S. corn, soybeans, pork, and beef, allowing them to lower their prices to foreign consumers.

As expected, the reverse is true of a strong U.S. dollar. As the U.S. dollar becomes more valuable relative to other currencies, a food importer can purchase more Peruvian blueberries for the same amount of dollars, allowing that importer to raise profits or lower prices and gain greater access to U.S. grocery shelves. Lower prices for foreign food products encourage consumers to buy more or try new items. This has been the case with U.S. consumers between 2020 and 2024, when the value of the U.S. dollar as measured by the broad DXY Index increased by more than 20%. The last two times the U.S. dollar increased as quickly as that, in the late 1990s and the mid-2010s, the U.S. food and agricultural trade balance almost fell into deficit, barely avoiding turning negative.

So, Now What?

Data indicates that the primary driver of the recent descent into a U.S. agricultural trade deficit is a hungry consumer armed with a strong dollar. As U.S. trade negotiations carry into the summer of 2025, analysts and economists will be eying not just retaliatory and reciprocal tariff levels, but also exchange rates and consumer economic health. Both factors may be equally important in driving the U.S. food and agricultural trade ledger back towards balance. If negotiations lead to increased market access or additional trade agreements, increasing agricultural exports could drive down the deficit. At the same time, U.S. consumers may have a challenging time giving up some imported goods: Just ask a loyal coffeehouse visitor on a Monday morning.