Laboring Over Agricultural Imports

As highlighted in Farmer Mac’s Feed article “What in the World? How the U.S. Became a Net Importer of Food and Agriculture”, in recent years, the U.S. agricultural sector has shifted from a long-standing trade surplus to contributing to the overall U.S. trade deficit. For most of the past century, agriculture was a net exporter. That trend continued as, more recently, growing exports of livestock products, fruits, and tree nuts drove U.S. agricultural exports upward, fueled by rising global demand for American-grown food. However, this trend has reversed, with the USDA projecting an agricultural trade deficit for the third consecutive year in 2025.

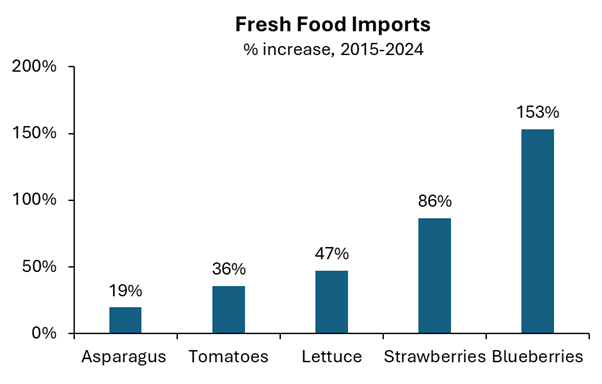

The U.S. primarily imports consumer-oriented products that require little or no further processing, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, cheeses, wines, juices, and other processed foods. In 2024, approximately 70% of U.S. imports were consumer-oriented—a proportion that remained largely consistent since 2000.

What’s Driving Imports?

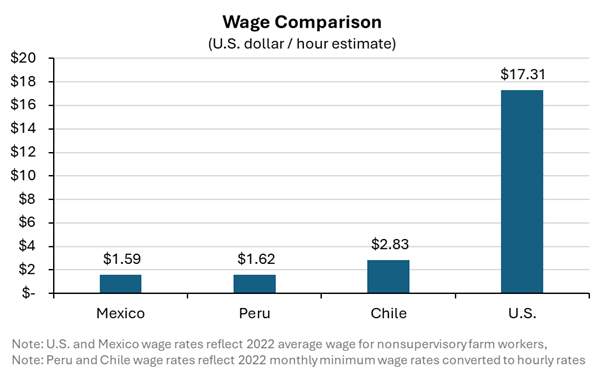

Several factors are driving the growth in U.S. agricultural imports, including consumer demand, the strength of the U.S. dollar, and improvements in the supply chain. However, one of the most significant drivers has been the wage disparity between countries.

Labor costs remain a significant expense for producers of numerous agricultural commodities, particularly for fruit and vegetable growers. While annual crop producers have long benefited from mechanized planters, harvesters, and sprayers to reduce manual labor, crops like those shown in the graph above require manual labor at multiple stages due to their lack of uniformity and delicate nature. As a result, producers of these labor-intensive crops are more vulnerable to fluctuations in labor market conditions, including wage changes.

U.S. agricultural imports have surged from countries with much lower wage rates. Mexico was the largest exporter of agricultural goods to the U.S. in 2024, shipping approximately $49 billion in products. Of these, approximately 92% were consumer-oriented, including tomatoes, lettuce, peppers, and more. Interestingly, the U.S. also produces and exports large volumes of many of these same goods. However, domestic production is significantly more costly due to wage rate disparities.

As of 2022, the average wage for nonsupervisory farm workers in Mexico was $1.59 per hour—91% lower than the U.S. average for the same year. The wage gap extends to several other countries as well. Peru, Chile, and others with low wage rates have seen agricultural exports to the U.S. explode in recent years. Part of the increase can be attributed to the inverse growing seasons for South American countries, which provide U.S. consumers with fresh produce during the winter months. However, since Mexico’s growing season largely aligns with the U.S., this suggests that producers are primarily benefiting from the wage rate disparity.

To illustrate the impact of lower wages, consider strawberry production. Labor is the largest production cost for California strawberry growers, making up more than 60% of operating costs. A 90% reduction in labor costs would boost operating margins by $50,000 or more per acre, according to 2024 enterprise budgets. While the example is extreme, it underscores how growers in Mexico can arbitrage the production cost difference. In fact, strawberry imports from Mexico topped $1.1 billion in 2024—an increase of 193% from 2015.

Reversing the Wage Deficit?

Dramatic wage differentials between countries present an obstacle to reversing the agricultural trade deficit. While tariffs on foreign agricultural goods could alleviate some of the pressure on U.S. producers of labor-intensive crops, the resulting increase in retail food prices is likely to be modest for many goods. Nonetheless, U.S. agricultural producers continue to contend with a tight domestic labor market and rising wage demands for H-2A employees. The development of mechanized planters and harvesters for labor-intensive crops could offer a solution, but the timeline for widespread commercialization remains uncertain. Until immigration reform and automation technology become a reality, U.S. producers will likely need to focus on managing labor costs as best they can.