Water

American producers have been adjusting to changing water supplies for decades. The USDA estimates that, even as total irrigated acres increased between 2013 and 2018, total water use declined 6%. This suggests that producers became more efficient in their irrigation methods, such as by using pressure sprinklers or drip systems. Even as technology has helped producers to become more efficient in how water is dispersed, issues with water access have been mounting, especially for producers in arid or semi-arid regions. Many farmers will face increasing constraints in the coming years, and more regions may become subject to new water conservation programs.

Risks related to water accessibility will range from the long term to the very short term, depending on the region. In general, though, water supplies have tightened considerably across the country.

One of the nation’s largest sources of fresh water, the Ogallala Aquifer, spans from the northern Great Plains down to northern Texas. The aquifer has seen considerable depletion since it first became an important resource for producers. However, most estimates believe that peak production is still several decades away, given current practices. This allows producers in this region some time to transition to more sustainable practices in the least disruptive way possible. Other areas have similar long-term risks. In Georgia, the USGS has found that water tables in major farming areas have fallen consistently over the last few decades. Water access has already led to lawsuits between Florida and Georgia that have reached the Supreme Court. These have been settled for now; in April 2021, the Supreme Court issued a ruling that select agricultural impacts in Florida could not be attributed to water misuse in Georgia.

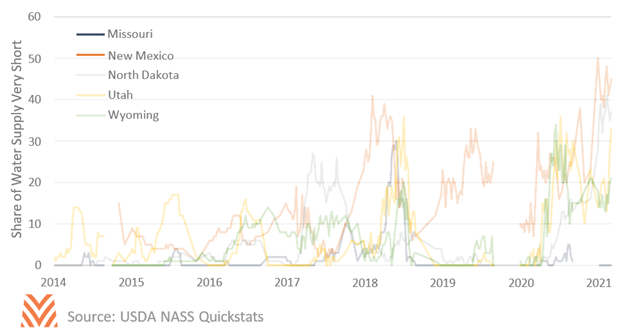

In California, producers face a very different and more pressing reality. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) is already leading to reductions in acre-foot allowances from local irrigation districts. Some districts have already experienced zero acre-foot allotments, which may lead to farmland transition if water continues to be scarce. Meanwhile, USDA NASS measurements have found that states from North Dakota to New Mexico are currently experiencing their shortest water supply on record.

While water has always been an important consideration for producers, water rights may become paramount in the coming years. Local policies will play a key role as state governments decide how to address declining water tables. Tightening supplies may harm crop yields or increase farm expenses, depending on how producers address shortages. In areas of chronic water undersupply, water may become the primary determinant in land values. This is already true in parts of California, where land with strong water access can see premiums up to 100% over county averages. California’s challenges may never occur in other regions, but producers and lenders in arid and semi-arid regions should recognize the potential for more permanent water constraints in the future.