Sour Grapes: Wine Consumption Decline Stresses Growers

‘Tis the season for holiday cheer! Unfortunately for U.S. vineyard owners, holiday feasts are likely to feature less wine this year. U.S. per capita alcohol consumption reached a 90-year low in 2024. A challenging concoction of shifting demographic preferences, health movements, non-alcoholic alternative drinks, and the increasing prevalence of weight loss drugs (i.e., GLP-1s) has resulted in significant headwinds for the entire alcohol industry in 2025. In fact, Gallup data in 2025 shows the proportion of U.S. adults who say they consume alcohol dropped to the lowest level in the survey’s 90-year history. Furthermore, according to Gallup data, nearly two-thirds of 18- to 34-year-olds say consuming alcohol is bad for their health, up from only 30% a decade ago. Despite the many perceived benefits of enjoying wine in moderation, it has not been immune to this trend.

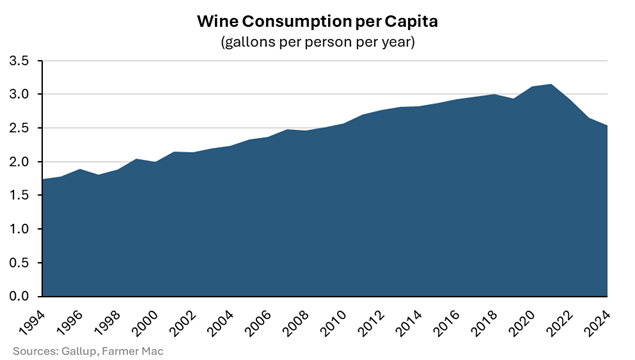

Wine consumption has trended lower in recent years, causing concerns about an oversupplied market. U.S. wine consumption trended higher for almost 80 years prior to 2021. According to the Wine Institute’s U.S. wine consumption statistics, from the mid-1930s to the early 2020s, per capita consumption increased by more than tenfold, boosted by greater availability, a broader variety of wines, and diet shifts that encouraged moderate wine consumption. In the 2020s, this long-term pattern has come to a screeching halt. U.S. wine consumption fell 20% since 2021 and may decline further still in 2025.

Similar to other permanent crops, wine grapes require a fair amount of forecasting, as vineyards take years before reaching full production. Historically, growers have been able to predict with reasonable accuracy what domestic consumption will look like several years down the road, and even what export demand might be. However, they still had plenty of decisions to make when choosing which grape variety to plant. Like apple varieties that have gone in and out of vogue, so have certain wine grape varieties. The current challenge facing the wine industry is the magnitude of the drop and the timespan over which it occurred. The combination of the two has led to significant profitability headwinds for many vineyard owners.

Lower Consumption, Lower Prices

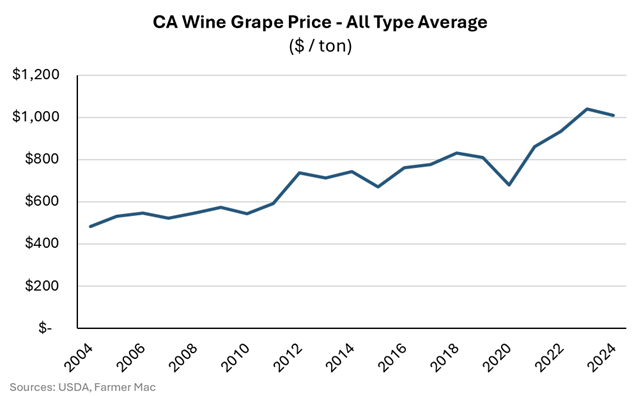

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the downward trend in wine consumption has spilled over into lower wine grape prices. According to the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) Preliminary Grape Crush Report, the average California wine grape price declined 3% per ton in 2024, the first decline since 2020. While this decline may not seem all that dramatic, it occurred despite a simultaneous drop in wine grape production. According to the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) Preliminary Grape Crush Report, the 2024 California grape harvest only totaled approximately 2.89 million tons—a 22% decline from 2023 and the smallest crop since 2004.

Wine grape producers contributed to the production pullback last year. For some producers, they had no choice but to reduce their production, as there were no buyers for their grapes. Others removed vines in anticipation of the 2024 price drop.

Unfortunately, this trend appears to be continuing in 2025. Some industry estimates suggest thousands of additional acres were removed from production before this fall’s wine grape harvest, although the official USDA data will not be released until next year. The removal of additional acres this year might provide some support for wine grape prices as the market seeks a new balance between supply and demand. However, the reported market price for wine grapes also fails to consider the acres of unsold grapes, which reportedly could surpass last year in quantity. Still, it is notable that not all wine grapes are faring the same, as there has been a clear divergence between high-end grape prices and cheaper varietals. High-end grapes have not experienced nearly as much price softening, but they still face pressure.

Table Grape Collateral Damage? Not so Much

The perils of the wine grape industry raise the question: What does this mean for table grapes? The good news is that the challenges for wine grape growers have had little impact on the table grape industry. In theory, wine grapes could be substituted for table grapes, but they would likely not fare well at retail stores. Wine grapes are smaller, with thicker skins and more seeds, making them less appealing to eat than modern table grapes.

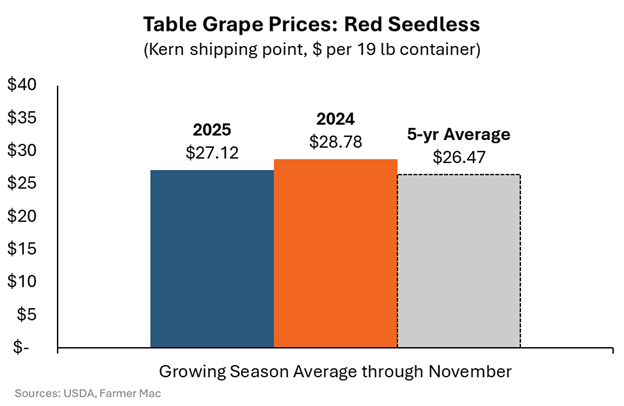

This isn’t to say that table grape producers haven’t faced challenges. Indeed, table grape prices have been relatively stagnant over the past couple of growing seasons. Prices for red seedless grapes, for example, have averaged modestly lower through November than the 2024 crop, while remaining slightly higher than the 5-year average.

The challenges for table grape producers have stemmed from other factors, such as rising labor costs and competition from imports. Labor remains a key challenge for many permanent crop producers, including table grape growers. Not only is labor increasingly scarce, but labor costs have surged in recent years, eating into margins already compressed by numerous inflationary factors. The dearth of an affordable labor pool has directly contributed to the increase in foreign grape imports. Some producers have relocated operations to Mexico or other countries with lower labor costs. While U.S. consumers have benefited from the lid that imports have kept on retail grape prices, U.S. table grape producers have been squeezed by rising costs and an inability to raise prices amid import competition.

Conclusion

The near-term challenges are undoubtedly daunting for many U.S. wine grape producers. Uncertainty about future wine demand remains elevated, especially when accounting for sectoral shifts in alcohol consumption. Furthermore, vineyard conversions are capital-intensive, and many producers may be reluctant to recommit to different grape varieties. So, will a future upswing in demand for U.S. wines need to originate from outside the U.S.? Export shipments have dropped significantly in 2025, partly in response to the U.S.’s widespread tariffs this year. Still, there are numerous markets where U.S. wines remain well-liked, and 2025 export shipments have increased, including in the Middle East and Asia. Perhaps a combination of continued growth in these markets, new U.S. trade deals, and a rebalancing of supply and demand could boost U.S. wine grape profitability.