Labor a Core Challenge for Apple Growers

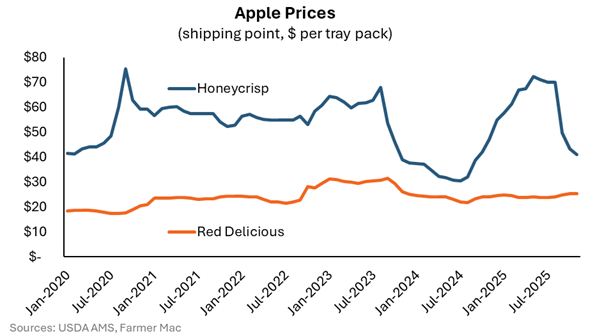

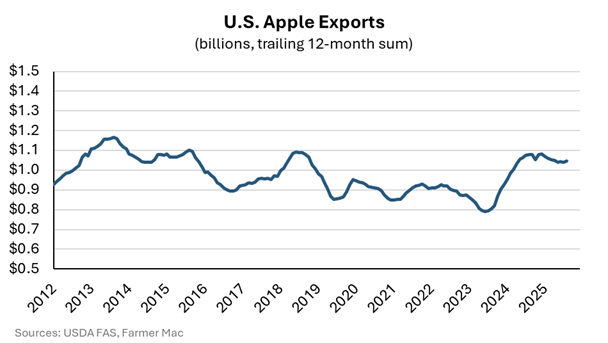

Following a year of modest price reprieve, apple growers enter the winter of 2025/26 in a period of heightened uncertainty. Apple prices rebounded momentarily during the 2024 crop year, albeit with a large variance across different varieties. Domestic apple consumption remains robust, especially for apple varieties that remain in vogue such as Honeycrisp. According to USDA AMS Market News, Honeycrisp farmgate prices more than doubled in 2024, while prices for Red Delicious and other classic varieties rose by more modest amounts. The price increases last year was partially a function of lower production. However, they also reflected a continued bounce back in global demand for U.S. apples. According to USDA FAS GATS, U.S. apple exports totaled more than $1 billion for the 2024 crop year, over 30% higher than 2023. Furthermore, 2024 was the first crop year since 2018 that exports surpassed $1 billion.

While the jump in export demand was welcomed by apple growers, maintaining consistent growth over the past decade has been a challenge. The U.S. apple industry has historically benefited from growing global demand for fresh produce, including apples. Estimates vary, but upwards of one-quarter of fresh apples harvested in the U.S. are exported in any given year. This proportion has grown through time as key markets such as Canada and Mexico have increased imports, helping absorb the growth in U.S. apple production and boosting prices. There are also several key markets outside of the immediate U.S. neighbors, including India and Japan.

Despite numerous tailwinds, exports have also been largely flat over the past decade. The U.S. is a global leader in apple genetics and helped pioneer numerous new varieties, including Honeycrisp, in the last several decades. These varieties have garnered a significant following among consumers both domestically and abroad, helping boost exports.

Unfortunately, periods of growth in apple exports over the past decade have been followed by setbacks. Trade disputes with key exporting countries have resulted in counter-tariffs on U.S. agricultural goods, including apples. Most famously, India was a top destination for U.S. apple exports before imposing counter-tariffs, leading to a 98% drop in imported U.S. apples the following year. Beyond trade disputes, the global supply chain disruption caused by COVID-19 also limited exporters’ ability to physically move apples overseas, even when demand existed. Finally, foreign competitors have been quick to capitalize on an inconsistent U.S. apple supply and have captured significant market share in the process.

While Prices Flatline, Labor Costs Continue to Climb

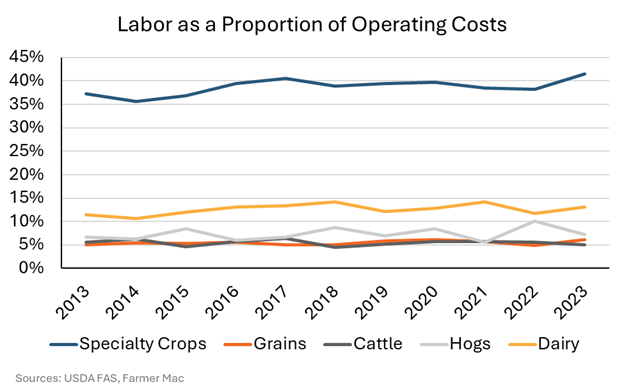

Apple producers continue to face the same significant hurdle that many other permanent crop producers have in the last several decades: labor. According to the USDA ERS Apple Sector Report, labor is the largest proportion of operating costs for specialty crop producers, accounting for nearly 40% over the past 10 years. This was over three times the same percentage for dairy, the next-closest production type. Estimates vary when examining apple labor costs because of differences in orchard types and varieties. However, the disparity persists and underscores an ongoing lack of mechanization across the apple sector and other specialty crops. While there is anticipation of mechanizing certain apple production tasks in the future—such as combining AI with advanced image sensors, which could expedite the rollout of mechanical harvesters—for now, mechanization is still particularly elusive for other tasks, and labor is likely to remain a key input component for apple growers for the foreseeable future.

Beyond labor being the largest component for specialty crop producers, its overall share continues to increase at the fastest rate among all producer types. This is largely attributable to specialty crop producers’ reliance on the H-2A program, where wages are predetermined. The U.S. Department of Labor annually calculates the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) as the minimum wage for H-2A workers. The AEWR is calculated for each state using USDA survey data, but tends to be higher than state and federal minimum wages. In the key apple-producing state of Washington, for example, the AEWR rose from $12.00 per hour in 2013 to $19.82 per hour in 2025, a 65% increase.

Conclusion

Apple growers have invested significantly in orchards over the past several decades, phasing out historic apple varieties for newer ones. Consumers have benefited from this investment, with an abundance of better-tasting varieties available in stores. However, farmgate apple prices have not increased fast enough to offset the surge in labor costs over the last decade, putting some growers in a precarious financial position. While the positive outlook for apple consumption is worth celebrating, a solution to the labor quagmire is likely to remain a top priority for many producers in 2026.