Grain and Oilseeds Prices Firm Amid Fears of Global Shortages

While consumers around the globe are battling inflation on almost every front, food price inflation presents perhaps the biggest threat to both emerging and advanced economies. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Food Price Index has increased by nearly 70% since the COVID-19 pandemic, the second-fastest rise in food prices in the last 30 years. A big part of that rise is an increase in commodity prices, particularly for wheat, corn, and soybeans. The principles of economics explain much of these gains in price, but farmers (and their lenders) are experiencing higher input prices that offset the gains in price. Luckily, the balance of these forces remains optimistic for 2022.

Supply

Wheat and corn markets got a bit of a jolt in early 2022 from a drop in expected global supplies. The war in Ukraine broke out during winter wheat dormancy and ahead of the spring planting season for corn and spring wheat. While the world may not know the full impact on Ukrainian corn and wheat production until the fall, damage and disruption to their agricultural infrastructure has been enough to erode expectations since March 2022. In May 2022, the USDA forecast declines of 34% and 53% in 2022 for Ukrainian wheat and corn production, respectively. While Ukraine ranks only tenth in the world in wheat production and ninth in corn production, they are a prominent exporter of those commodities—in 2021, Ukrainian producers exported 79% of their corn crop and 66% of their wheat crop. In addition to these threats to production posed by the Ukrainian conflict, strained shipping lanes are creating stress on food supply chains in much of Africa and parts of Asia, pushing up food prices and creating a humanitarian food security crisis in many poorer countries.

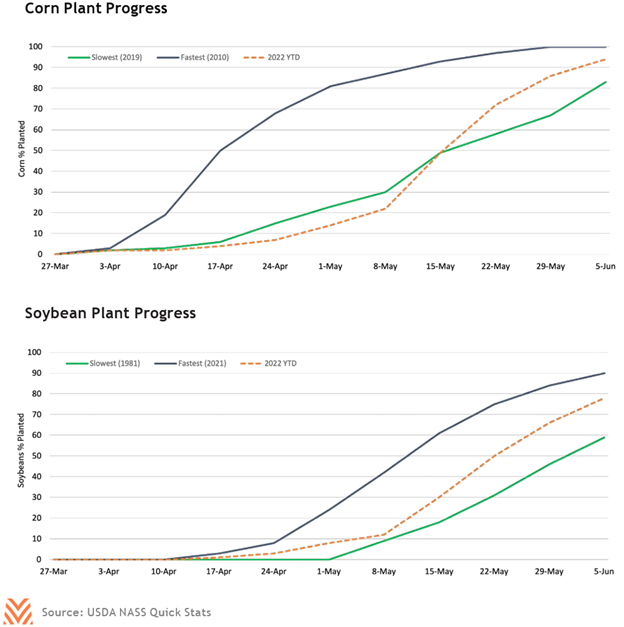

U.S. production faced some early concerns due to a cool, wet start to spring, but producers bounced back in May and June. Planting progress for both corn and soybeans started the season at the worst (or nearly the worst) in 42 years. However, as the figure below highlights, better weather in May and June allowed growers to catch up quickly. Winter wheat conditions remain bearish, with reported crop conditions at their lowest levels since 2014 and the spring wheat plant approximately two weeks behind normal levels. Finally, soybeans have the best prospect of rebuilding global supplies this year, with very large crops already from Brazil and expected from the U.S. in the fall.

Demand

Despite higher prices, demand for grains and oilseeds has kept pace. With the production declines in Ukraine, the world will rely more on other producing regions, like the U.S., Europe, Australia, and even Russia to feed their populations. High fuel costs have helped ethanol producers stay profitable in rising corn prices. Soybean exports remain stalwart, but an expected increase of 20% in soybean oil usage for biofuels and renewable diesel helps boost domestic demand for beans. Rising prices for animal proteins like pork, dairy, poultry, and beef also help support higher feed prices. Overall, demand fundamentals are healthy even in a high-price environment.

Risks Ahead

The most significant risk for farmers for the remainder of this year and into next is the rising price of practically everything. Input prices for seed, fertilizer, and chemicals are up sharply in 2022. While fertilizer prices could pause for the short term, they are unlikely to retreat, given high energy prices and trade disruptions from Russia. Combined with land costs and rising rental rates, the cost to plant an acre of corn, wheat, or soybeans will almost certainly increase in 2023. Lenders may see additional credit drawn to help with capital costs, but they too have higher input costs with rising interest rates. Growers and their lenders should start preparing for 2023 and 2024, when commodity prices might ease—but input costs may be slower to respond.