A Brief History of (ITC and PTC) Time

In the world of renewable energy, few policy tools have had as much impact as the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) and Production Tax Credit (PTC). These federal tax incentives have powered the rise of wind and solar energy in the U.S. for nearly five decades. But under the recently enacted House Resolution 1 (HR1, a.k.a., the One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act), these credits are now scheduled to sunset, marking a pivotal moment in U.S. energy build-out.

What are the ITC and PTC?

The ITC provides a tax credit based on the upfront capital cost of eligible energy projects such as solar panels and battery storage. The PTC, on the other hand, is based on electricity production, primarily benefiting wind farms and other generation technologies.

Since their inception (1978 for the ITC and 1992 for the PTC), these credits have been extended, modified, and allowed to expire numerous times. HR1 now sets a firm expiration, transitioning the credits to a technology-neutral format before phasing them out entirely by the mid-2030s or sooner.

A Rollercoaster of Policy

The legislative history of these credits includes several starts and stops. The ITC began as a modest 10% credit that grew to 30% and was repeatedly extended, often at the eleventh hour. The PTC, meanwhile, has seen significant policy uncertainty over its life, expiring and reviving multiple times, each lapse causing a sharp drop in wind project development.

Despite the volatility, the credits have been remarkably effective. According to the NC Clean Energy Technology Center and Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the ITC and PTC have mobilized over $300 billion in private investment, created hundreds of thousands of jobs, and helped drive industry scale necessary to push down the cost of wind and solar by over 70% and 90%, respectively, since 2009.

Critics in the Wings

While ITC and PTC have been effective at driving investment in renewable power projects, not everyone is supportive of the tax credit structure. Economists have long debated the efficiency of these credits. Critics argue they distort electricity markets and land development economics, contribute to negative pricing, and favor certain technologies over others. The CBO estimates that before the enactment of HR1, the credits would have reduced near-term tax revenue by $308 billion from 2026 to 2035. And yet, the CBO acknowledges that two-thirds of the investments would have occurred without the credits—a testament to how far renewables have come.

What Happens When the Sun Sets?

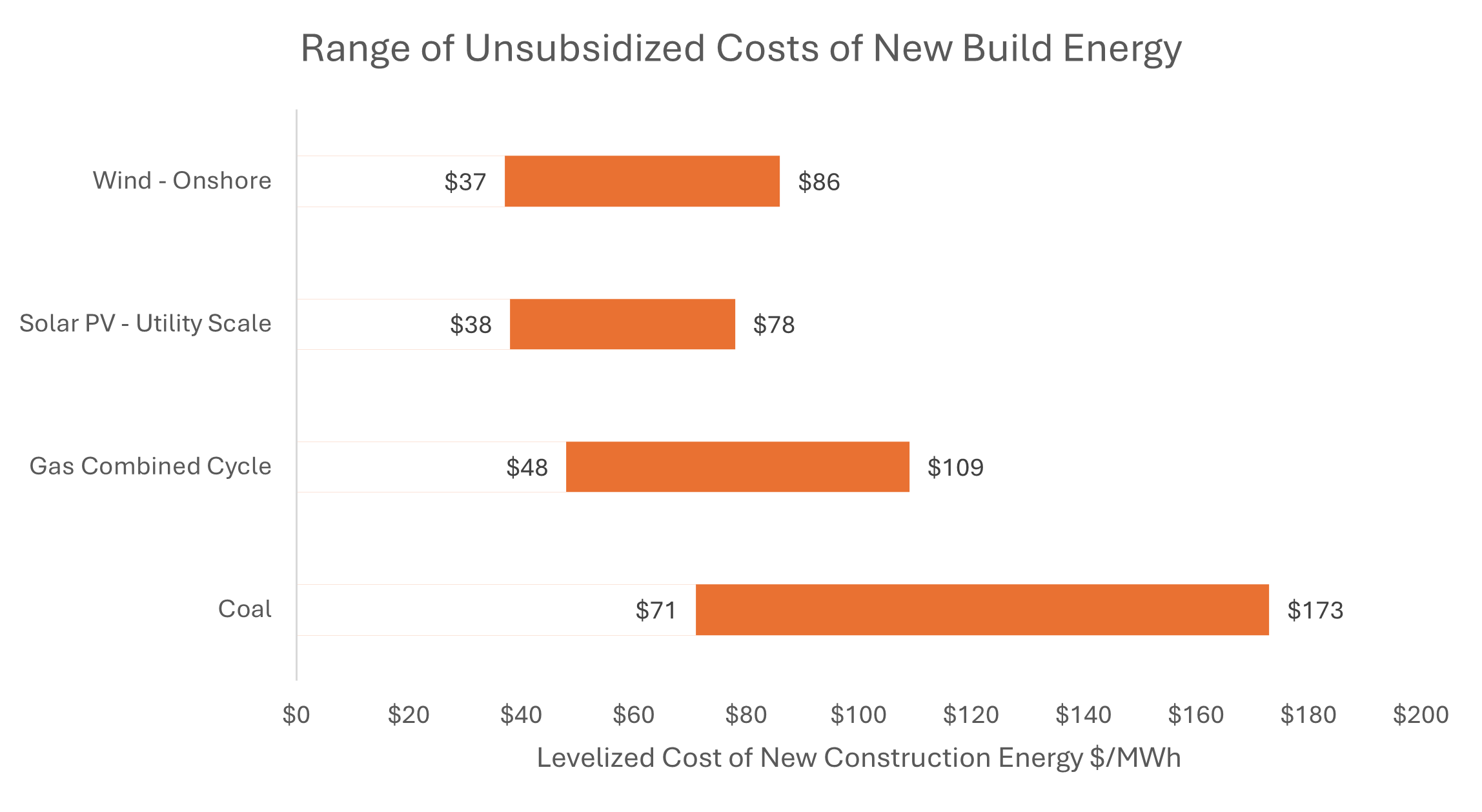

If HR1’s sunset provisions hold, the renewable energy sector is likely to face potential capital sourcing challenges. Subsidies to promote new electricity generation help increase the supply of power and reduce the cost of that power. Without the ITC and PTC programs, consumers could bear the higher power costs of both renewables and older technologies that will remain on the grid for longer. But that isn’t the end of the story: The 2025 Lazard Levelized Cost of Energy+ report shows that unsubsidized wind and solar remain the cheapest forms of new electricity generation in most U.S. markets. Even without the ITC and PTC, renewables are expected to remain competitive, especially as battery storage, grid modernization, and domestic manufacturing continue to scale.

In Conclusion (or To Be Continued?)

The ITC and PTC have long served as market-altering incentives, helping to accelerate the deployment of wind and solar technologies by reducing upfront and operational costs. As these credits begin to phase out under HR1, the energy sector enters a new phase—one where investment decisions will increasingly be guided by market fundamentals rather than tax incentives.

While the expiration of these credits may raise capital and production costs in the near term, the broader alignment of market forces remains favorable. If the CBO analysis is correct, two-thirds of renewable power projects will still be deployed. With unsubsidized wind and solar now among the most cost-competitive and quickest-to-deliver sources of new electricity generation, unit economics may continue to support further buildout.

The evolution of these credits reflects a broader shift: from policy-driven deployment to market-centered momentum. As cost curves flatten and technologies mature, the role of federal incentives may diminish, but the underlying economic rationale for investment in new generation remains strong. And with the expected dramatic rise in electricity demand hitting the grid in the coming years, higher electricity prices may help cover up the higher capital costs from any missing tax incentive programs.

If the future even remotely rhymes with the past, the expiration of the ITC and PTC tax credits could mark their final chapter—or perhaps set the stage for their next revival, as market forces and policy priorities continue to evolve.

Policy History and Timeline

-

1978 – Energy Tax Act of 1978

Genesis of the ITC. In response to the 1970s energy crisis, President Jimmy Carter signed the Energy Tax Act, establishing the first federal tax credits for renewable energy. A 10% Investment Tax Credit was created for solar and wind energy investments (and it was even refundable in its first years). On the residential side, homeowners could get credits for installing solar equipment (called the Residential Energy Credit, 30% of the first $2,000 in costs).

-

1980 – Windfall Profit Tax Act

Expansion of Credits. The credit for renewable energy was increased. The Residential Energy Credit’s value was raised up to 40% for solar systems (with caps). The business ITC for solar/wind was also increased to 15% and made non-refundable, reflecting continued support for alternative energy through the end of Carter’s term.

-

1985 – Expiration during Reagan Administration

Pullback. By the mid-1980s, oil prices had fallen and political support for renewables waned. The residential solar tax credit was allowed to expire at the end of 1985. Federal ITC for businesses also effectively ended for wind (wind was removed from ITC eligibility in 1986). These expirations led to a sharp decline in solar installations in the late 1980s. The renewable energy industry entered a lull without federal incentives.

-

1992 – Energy Policy Act of 1992

Birth of the PTC. With concerns about energy and environmental security rising, Congress passed a comprehensive energy bill in 1992. This act introduced the Production Tax Credit (PTC) for the first time, initially for wind power and a few other renewables. The PTC was set at 1.5¢/kWh for the first 10 years of generation for projects in service by July 1999. The 1992 Act also permanently extended a modest 10% ITC for solar (which had been intermittently renewed through the late ’80s). At this point, the modern framework of investment vs. production credits was established.

-

1999–2004 – PTC Lapses and Renewals

Boom-Bust Begins. The wind PTC was initially authorized only through mid-1999. Congress allowed it to expire in July 1999, then revived it in December 1999 for a few more years. This pattern repeated: The PTC lapsed again at end of 2001 and 2003, each time causing a pause in wind project development until the credit was retroactively extended. These repeated last-minute extensions created uncertainty, and wind installations dropped sharply in years when the PTC was not in effect. Despite this, by 2004 the U.S. wind industry was slowly growing, aided also by emerging state policies (like Texas’s 1999 Renewable Portfolio Standard).

-

2005 – Energy Policy Act of 2005

Revival of ITC & Long-Term Extension. This landmark energy bill under President George W. Bush boosted the ITC to 30% for solar energy investments. A new 30% residential solar tax credit was also created (capped at $2,000). Though initially set to last only through 2007, this high-value ITC jump-started the modern U.S. solar industry. The 2005 law also extended the PTC for wind and other renewables for two more years, providing stability through the end of 2007. This period marks the beginning of rapid growth in renewable generation investment, thanks to generous, long-term incentives.

-

2008–2009 – Emergency Extensions and ARRA

Financial Crisis Response. The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (the bank bailout bill) included an 8-year extension of the solar ITC (through 2016) and removed the $2,000 cap for residential systems, signaling strong federal commitment to clean energy. Then, in early 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) addressed new problems: The recession had reduced the number of investors who could use tax credits. ARRA allowed renewable developers to take a 30% cash grant in lieu of the ITC (the Section 1603 program) and allowed PTC-eligible projects (like wind) to opt for the 30% ITC instead. This effectively kept project finance flowing during the downturn by using grants. ARRA also extended the PTC fully through 2012. These measures led to a renewable investment surge despite the recession.

-

2013–2015 – Avoiding the “Fiscal Cliff” & Phase-Down Plans

Policy Tweaks and Stability. In January 2013, as part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act, Congress changed the PTC’s rules: Projects now qualified if construction started by the deadline (end of 2013), rather than being fully operational, making it easier for developers to use the incentive in time. After another brief lapse in 2014 (quickly restored retroactively), a major budget deal in December 2015 provided a long-term outlook: The PTC for wind was extended for five years through 2019, with a gradual phase-down in value (20% reduction per year in the last three years). Simultaneously, the solar ITC was extended at 30% through 2019, with a scheduled step-down to 26% in 2020, 22% in 2021, and then 10% thereafter for commercial (0% for residential). This 2015 legislation gave the industry a clear runway and reduced the uncertainty that had plagued it for years.

-

2018–2021 – Incremental Extensions

Further Tweaks. In 2018, and again in late 2019 and 2020, Congress passed additional extensions. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 preserved tax credits for some orphaned renewables and extended the wind PTC phase-down timeline (allowing wind projects starting construction in 2020 to still qualify at a reduced credit). The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2020 (Dec 2019) and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (Dec 2020) each added one more year to the PTC/ITC deadlines for wind and kept the solar ITC at 26% through 2022. By the end of 2021, wind’s PTC was scheduled to fully sunset for new projects, and solar’s ITC was set to drop to 22% (with expiration for residential) in 2023. Despite the step-down, renewable deployment continued at record levels as developers rushed to qualify for credits.

-

2022 – The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

Game Changer & New Era. In August 2022, the IRA was enacted, representing the largest climate and clean energy investment in U.S. history. This law extended the ITC and PTC through at least 2032 and revamped them into a technology-neutral form after 2024. The credits returned to 30% (ITC) and ~1.5¢/kWh (PTC) for a 10-year period, with bonus credits available for projects meeting domestic content, local economic, and labor criteria. Importantly, the IRA set the credits to phase down only when national greenhouse gas emissions from electricity are cut by 75% below 2022 levels (or after 2035), rather than expiring on a fixed date. This long-term certainty is designed to spur a massive wave of investment in clean power by removing the perennial policy uncertainty. It also allows projects of any low-carbon technology to choose either credit type going forward, and made credits more accessible (e.g. transferable, and for some entities, refundable). The industry entered 2025 with unprecedented clarity that federal support for clean energy will be sustained over the next decade and beyond.